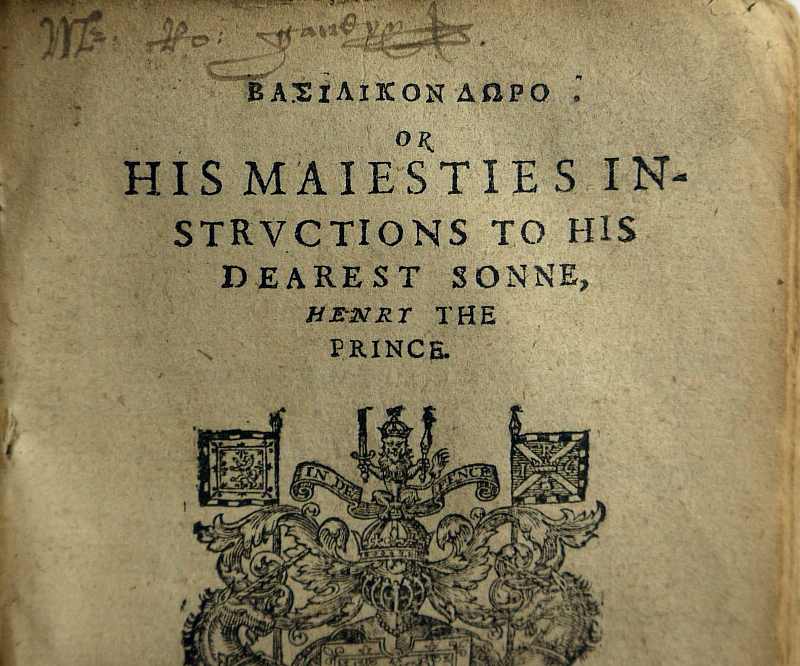

Basilikon Doron or His Majesty’s Instructions to his dearest son, Henry the Prince Written by King James I, Edition of Edinburgh, 1599.

The Dedication of the Book Sonnet

Lo here (my son) a mirror view and fair

Which showeth the shadow of a worthy King. Lo here a Book, a pattern doth you bring

Which ye should press to follow more and more This trusty friend, the truth will never spare, But give a good advice unto you here:

How it should be your chief and princely care, To follow virtue; vice for to forbear.

And in this Book your lesson will ye learn,

For guiding of your people great and small. Then (as ye ought) give an attentive care,

And think how ye these precepts practice shall. Your father bids you study here and read

How to become a perfect King indeed.

The Argument of the Book Sonnet

God gives not Kings the style of God’s in vain, For on His throne His scepter do they sway:

So Kings should fear and serve their God again. If then ye would enjoy a happy reign,

Observe the statutes of your Heavenly King; And from His laws make all your laws to spring: Since His lieutenant hre ye should remain. Reward the just, be steadfast, true and plain: Repress the proud, maintaining always the right, Walk always so, as ever in His sight

Who guards the godly, plaguing the profane, And so ye should in princely virtues shine, Remembering right your mighty King Divine.

To Henry my Dearest Son and Natural Successor

To whom can so rightly appertain his book of the Instruction of a Prince in all the points of his calling, as well general (as a Christian towards God) as particular (as a King towards his people?) to whom (I say can it so justly appertain, as unto you my dearest son? Since I, the author thereof, as your natural father, must be careful for your godly and virtuous education as my eldest son, and the first fruits of God’s blessing towards me in my posterity: And as a King) must faithfully provide for your training up in all the points of a King’s office (since ye are my natural and lawful successor therein) that being rightly informed hereby of the weight of your burden ye may in time begin to consider, that being born to be a King, ye are rather born to ONUS, than HONOS: not excelling all your people so far in rank and honour, as in daily care and hazardous painstaking, for the dutiful administration of that great office that God hath laid upon your shoulders: laying so, a just symmetry and proportion, betwixt the height of your honourable place, and the heavy weight of your great charge: and consequently in case of failure (which God forbid) of the sadness of your fall, according to the proportion of that height.

I have therefore (for the greater ease of your memory, and that ye may at the first, cast up any part that ye have to do with) divided this whole book in three parts. The first teacheth you your duty towards God as a Christian: The next your duty in your office as a King: and the third teacheth you how to behave yourself in indifferent things, which of themselves are neither right nor wrong, but according as they are rightly or wrongly used: and yet will serve (according to your behavior therein) to augment or impair your fame and authority at the hands of your people. Receive and welcome this book then, as a faithful preceptor and counsellour unto you: which (because my affairs will not permit me ever to be present with you). I ordain to be a resident faithful admonisher to you. And because the hour of death is uncertain to me (as unto all flesh) I leave it as my Testament, and latter Will unto you: charging you in the presence of God, and by the fatherly authority I have over you, that ye keep it ever with you, as carefully as Alexander did the Iliades of Homer. Ye will find it a just and impartial Counsellour, neither flattering you in any vice, nor importuning you at unmet times: It will not come uncalled, nor speak unspoken at: and yet conferring with it when ye are quiet, ye shall say with SCIPIO, that Nunquam minus solus, quam cum solus.

To conclude, then, I charge you (as ever ye think to deserve my fatherly blessing) to follow and put in practice (as far as lyeth in you) the precepts hereafter following: and if ye follow the contrary course, I take the great God to record, that this book shall one day be a witness betwixt me and you, land shall procure to be ratified in heaven, the curse that in that case here I give you; for I protest before that great God, I had rather be not a father and childless, nor be father of wicked children. But (hoping, yea, even promising unto myself, that God who in His great blessing sent you unto me, shall in the same blessing, as He hath given me a son, not repenting Him of His mercy shown unto me), I end this preface with my earnest prayer to God, to work effectually unto you, the fruits of that blessing which here from my heart, I bestow upon you.

Finis.

OF A KING’S CHRISTIAN DUTY TOWARDS GOD

THE FIRST BOOK

As he cannot be thought worthy to rule and command others, that cannot rule and subdue his own proper affections and unreasonable appetites, so can he not be thought worthy to govern a Christian people, knowing and fearing God, that in his own person and heart, feareth not and loveth not the Divine Majesty. Neither can any thing in his government succeed well with him, (devise and labor as he list) as coming from a filthy spring, if his person be unsanctified: for (as that royal Prophet saith) Except the Lord build the house, they labor in vain that build it: except the Lord keep the City, the keepers watch it in vain; in respect the blessing of God hath only power to give the success thereunto: and as Paul saith, he planteth, Apollos watereth; but it is God only that giveth the increase. Therefore (my Son) first of all things, learn to know and love that God, whom-to ye have a double obligation; first, for that he made you a man; and next, for that he made you a little GOD to sit on his Throne, and rule over other men. Remember, that as in dignity he hath erected you above others, so ought ye in thankfulness towards him, go as far beyond all others. A moat in another’s eye, is a beam into yours: a blemish in another, is a leprous bile into you: and a venial sin (as the Papists call it) in another, is a great crime unto you. Think not therefore, that the highness of your dignity, diminisheth your faults (much less giveth you a licence to sin) but by the contrary your fault shall be aggravated, according to the height of your dignity; any sin that ye commit, not being a single sin procuring but the fall of one; but being an exemplar sin, and therefore drawing with it the whole multitude to be guilty of the same. Remember then, that this glistering worldly glory of Kings, is given them by God, to teach them to press so to glister and shine before their people, in all works of sanctification and righteousness, that their persons as bright lamps of godliness and virtue, may, going in and out before their people, give light to all their steps. Remember also, that by the right knowledge, and fear of God (which is the beginning of Wisdom, as Salomon saith), ye shall know all the things necessary for the discharge of your duty, both as a Christian, and as a King; seeing in him, as in a mirror, the course of all earthly things, whereof he is the spring and only mover.

Now, the only way to bring you to this knowledge, is diligently to read his word, and earnestly to pray for the right understanding thereof. Search the Scriptures, saith Christ, for they bear testimony of me: and, the whole Scripture, saith Paul, is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable to teach, to convince, to correct, and to instruct in righteousness; that the man of God may be absolute, being made perfect unto all good works. And most properly of any other, belongeth the reading thereof unto Kings, since in that part of Scripture, where the godly Kings are first made mention of, that were ordained to rule over the people of God, there is an express and most notable exhortation and commandment given them, to read and meditate in the Law of God. I join to this, the careful hearing of the doctrine with attendance and reverence: for, faith cometh by hearing, saith the same Apostle. But above all, beware ye wrest not the word to your own appetite, as over many do, making it like a bell to sound as ye please to interpret: but by the contrary, frame all your affections, to follow precisely the rule there set down.

The whole Scripture chiefly containeth two things: a command, and a prohibition, to do such things, and to abstain from the contrary. Obey in both; neither think it enough to abstain from evil, and do no good; nor think not that if ye do many good things, it may serve you for a cloak to mix evil turns therewith. And as in these two points, the whole Scripture principally consisteth, so in two degrees standeth the whole service of God by man: interior, or upward; exterior, or downward: the first, by prayer in faith towards God; the next, by works flowing therefrom before the world: which is nothing else, but the exercise of Religion towards God, and of equity towards your neighbor.

As for the particular points of Religion, I need not to dilate them; I am no hypocrite, follow my footsteps, and your own present education therein. I thank God, I was never ashamed to give account of my profession, howsoever the malicious lying tongues of some have traduced me: and if my conscience had not resolved me, that all my Religion presently professed by me and my kingdom, was grounded upon the plain words of the Scripture, without the which all points of Religion are superfluous, as any thing contrary to the same is abomination, I had never outwardly avowed it, for pleasure or awe of any flesh.

And as for the points of equity towards your neighbor (because that will fall in properly, upon the second part concerning a King’s office) I leave it to the own room.

For the first part then of man’s service to his God, which is Religion, that is, the worship of God according to his revealed will, it is wholly grounded upon the Scripture, as I have already said, quickened by faith, and conserved by conscience: For the Scripture, I have now spoken of it in general, but that ye may the more readily make choice of any part thereof, for your instruction or comfort, remember shortly this method.

The whole Scripture is dictated by God’s Spirit, thereby, as by his lively word, to instruct and rule the whole Church militant to the end of the world: It is composed of two parts, the Old and New Testament: The ground of the former is the Law, which sheweth our sin, and containeth justice: the ground of the other is Christ, who pardoning sin containeth grace. The sum of the Law is the ten Commandments, more largely related in the books of Moses, interpreted and applied by the Prophets; and by the histories, are the examples shewed of obedience or disobedience thereto, and with the history of the infancy and first progress of the Church is contained in their Acts.

Would ye then know your sin by the Law? Read the books of Moses containing it. Would ye have a commentary thereupon? Read the Prophets, and likewise the books of the Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, written by that great pattern of wisdom Solomon, which will not only serve you for instruction, how to walk in the obedience of the Law of God, but is also so full of golden sentences, and moral precepts, in all things that can concern your conversation in the world, as among all the profane Philosophers and Poets, ye shall not find so rich a storehouse of precepts of natural wisdom, agreeing with the will and divine wisdom of God. Would ye see how good men are rewarded, and wicked punished? look the historical parts of these same books of Moses, together with the histories of Joshua, the Judges, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, and Job: but especially the books of the Kings and Chronicles, wherewith ye ought to be familiarly acquainted: for there shall ye see your self, as in a mirror, in the catalogue either of the good or the evil Kings.

Would ye know the doctrine, life, and death of our Saviour Christ? Read the Evangelists. Would ye be more particularly trained up in his School? Meditate upon the Epistles of the Apostles. And would ye be acquainted with the practices of that doctrine in the persons of the primitive Church? Cast up the Apostles Acts. And as to the Apocrypha books, I omit them, because I am no Papist, as I said before; and indeed some of them are no ways like the dictation of the Spirit of God.

But when ye read the Scripture, read it with a sanctified and chaste heart: Admire reverently such obscure places as ye understand not, blaming only your own capacity: read with delight the plain places, and study carefully to understand those that are somewhat difficult: press to be a good textualist; for the Scripture is ever the best interpreter of it self; but press not curiously to seek out farther than is contained therein; for that were over unmannerly a presumption, to strive to be further upon God’s secrets, than he hath will ye be; for what he thought needful for us to know, that hath he revealed there: And delight most in reading such parts of the Scripture, as may best serve for your instruction in your calling; rejecting foolish curiosities upon genealogies and contentions, which are but vain, and profit not, as Paul saith.

Now, as to Faith, which is the nourisher and quickner of Religion, as I have already said, It is a sure persuasion and apprehension of the promises of God, applying them to your soul: and therefore may it justly be called, the golden chain that linketh the faithful soul to Christ: And because it groweth not in our garden, but is the free gift of God, as the same Apostle saith, it must be nourished by prayer, Which is nothing else, but a friendly talking with God.

As for teaching you the form of your prayers, the Psalms of David are the most proper school-master that ye can be acquainted with (next the prayer of our Saviour, which is the only rule of prayer) where out of, as of most rich and pure fountains, ye may learn all forms of prayer necessary for your comfort at all occasions: And so much the fitter are they for you, than for the common sort, in respect the composer thereof was a King: and therefore best behooved to know a King’s wants, and what things were most proper to be required by a King at God’s hand for remedy thereof.

Use often to pray when ye are quietest, especially forget it not in your bed how oft soever ye do it at other times: for public prayer serveth as much for example, as for any particular comfort to the supplicant.

In your prayer, be neither over strange with God, like the ignorant common sort, that prayeth nothing but out of books, nor yet over homely with him, like some of the vain Pharisaical puritans, that think they rule him upon their fingers: The former way will breed an uncouth coldness in you towards him, the other will breed in you a contempt of him. But in your prayer to God speak with all reverence: for if a subject will not speak but reverently to a King, much less should any flesh presume to talk with God as with his companion.

Crave in your prayer, not only things spiritual, but also things temporal, sometimes of greater, and sometimes of less consequence; that ye may lay up in store his grant of these things, for confirmation of your faith, and to be an earnest unto you of his love. Pray, as ye find your heart moveth you, pro re nata: but see that ye ask no unlawful things, as revenge, lust, or such like: for that prayer can not come of faith: and whatsoever is done without faith, is sin, as the Apostle saith.

When ye obtain your prayer, thank him joyfully therefore: if otherwise, bear patiently, pressing to win him with importunity, as the widow did the unrighteous Judge: and if notwithstanding thereof ye be not heard, assure your self, God foreseeth that which ye ask is not for your good: and learn in time, so to interpret all the adversities that God shall send unto you; so shall ye in the midst of them, not only be armed with patience, but joyfully lift up your eyes from the present trouble, to the happy end that God will turn it to. And when ye find it once so fall out by proof, arm your self with the experience thereof against the next trouble, assuring your self, though ye cannot in time of the shower see through the cloud, yet in the end shall ye find; God sent it for your good, as ye found in the former.

And as for conscience, which I called the conserver of Religion, It is nothing else, but the light of knowledge that God hath planted in man, which ever watching over all his actions, as it beareth him a joyful testimony when he does right, so choppeth it him with a feeling that he hath done wrong, when ever he committeth any sin. And surely, although this conscience be a great torture to the wicked, yet is it as great a comfort to the godly, if we will consider it rightly. For have we not a great advantage, that have within ourselves while we live here, a Count-book and Inventory of all the crimes that we shall be accused of, either at the hour of our death, or at the Great day of judgement; which when we please (yea though we forget) will strike, and remember us to look upon it; that while we have leisure and are here, we may remember to amend; and so at the day of our trial, compare with new and white garments washed in the blood of the Lamb, as S. John saith. Above all then, my Son, labor to keep sound this conscience, which many prattle of, but over few feel: especially be careful to keep it free from two diseases, wherewith it useth oft to be infected; to wit, Leprosy, and Superstition; the former is the mother of Atheism, the other of Heresies. By a leprous conscience, I mean a cauterized conscience, as Paul calleth it, being become senseless of sin, through sleeping in a careless security as King David’s was after his murder and adultery, ever til he was wakened by the Prophet Nathan’s similitude. And by superstition, I mean, when one restrains himself to any other rule in the service of God, than is warranted by the word, the only true square of God’s service.

As for a preservative against this Leprosy, remember every once in the four and twenty hours, either in the night, or when ye are at greatest quiet, to call yourself to account of all your last day’s actions, either wherein ye have committed things ye should not, or omitted the things ye should do, either in your Christian or Kingly calling: and in that account, let not your self be smoothed over with that flattering ~tXcuyutcL, which is overkindly a sickness to all mankind: but censure your self as sharply, as if ye were your own enemy: For if ye judge yourself, ye shall not be judged, as the Apostle saith: and then according to your censure, reform your actions as far as ye may, eschewing ever wilfully and wittingly to contrary your conscience: For a small sin wilfully committed, with a deliberate resolution to break the bridle of conscience therein, is far more grievous before God, than a greater sin committed in a sudden passion, when conscience is asleep. Remember therefore in all your actions, of the great account that ye are one day to make: in all the days of your life, ever learning to die, and living every day as it were your last;

Omnem crede diem tibi diluxisse supremum.

And therefore, I would not have you to pray with the Papists, to be preserved from sudden death, but that God would give you grace so to hue, as ye may every hour of your life be ready for death: so shall ye attain to the virtue of true fortitude, never being afraid for the horror of death, come when he list: And especially, beware to offend your conscience with use of swearing or lying, suppose but in jest; for others are but a vice, and a sin clothed with no delight nor gain, and therefore the more inexcusable even in the sight of men: and lying cometh also much of a vile use, which will banish shame: Therefore beware even to deny the truth, which is a sort of lie, that may best be eschewed by a person of your rank. For if any thing be asked at you that ye think not meet to reveal, if ye say, that question is not pertinent for them to ask, who dare examine you further? and using sometimes this answer both in true and false things that shall be asked at you, such unmannerly people will never be the wiser thereof.

And for keeping your conscience sound from that sickness of superstition, ye must neither lay the safety of your conscience upon the credit of your own conceits, nor yet of other men’s humors, how great doctors of Divinity that ever they be; but ye must only ground it upon the express Scripture: for conscience not grounded upon sure knowledge, is either an ignorant fantasy, or an arrogant vanity. Beware therefore in this case with two extremities: the one, to believe with the Papists, the Churches authority, better than your own knowledge; the other, to lean with the Anabaptists, to your own conceits and dreamed revelations.

But learn wisely to discern betwixt points of salvation and indifferent things, betwixt substance and ceremonies; and betwixt the express commandment and will of God in his word, and the invention or ordinance of man; since all that is necessary for salvation is contained in the Scripture: For in any thing that is expressly commanded or prohibited in the book of God, ye cannot be over precise, even in the least thing; counting every sin, not according to the light estimation and common use of it in the world, but as the book of God counteth of it. But as for all other things not contained in the Scripture, spare not to use or alter them, as the necessity of the time shall require. And when any of the spiritual office-bearers in the Church, speak unto you any thing that is well warranted by the word, reverence and obey them as the heralds of the most high God: but, if passing that bounds, they urge you to embrace any of their fantasies in the place of God’s word, or would color their particulars with a pretended zeal, acknowledge them for no other than vain men, exceeding the bounds of their calling; and according to your office, gravely and with authority redact them in order again.

To conclude then, both this purpose of conscience, and the first part of this book, keep God more sparingly in your mouth, but abundantly in your heart; be precise in effect, but social in show: declare more by your deeds than by your words, the love of virtue and hatred of vice: and delight more to be godly and virtuous indeed, than to be thought and called so; expecting more for your praise and reward in heaven, than here: and apply to all your outward actions Christ’s command, to pray and give your alms secretly: So shall ye on the one part be inwardly garnished with true Christian humility, not outwardly (with the proud Pharisee) glorying in your godliness; but saying, as Christ commandeth us all, when we have done all that we can, Inutiles serui sumus: And on the other part, ye shall eschew outwardly before the world, the suspicion of filthy proud hypocrisy, and deceitful dissimulation.

End of the First Book

OF A KING’S DUTY IN HIS OFFICE

THE SECOND BOOK

BUT as ye are clothed with two callings, so must ye be alike careful for the discharge of them both: that as ye are a good Christian, so ye may be a good King, discharging your Office (as I showed before) in the points of justice and Equity: which in two sundry ways ye must do: the one, in establishing and executing, (which is the life of the Law) good Laws among your people: the other, by your behavior in your own person, and with your servants, to teach your people by your example: for people are naturally inclined to counterfeit (like apes) their Prince’s manners, according to the notable saying of Plato, expressed by the Poet

Componitur orbis Regis ad exemplum, nec sic inflectere sensus Humanos edicta valent, quam vita regentis.

For the part of making, and executing of Laws, consider first the true difference betwixt a lawful good King, and an usurping Tyrant, and ye shall the more easily understand your duty herein: for contraria iuxta seposita magis elucescunt. The one acknowledgeth himself ordained for his people, having received from God a burden of government, whereof he must be countable: the other thinketh his people ordained for him, a prey to his passions and inordinate appetites, as the fruits of his magnanimity: And therefore, as their ends are directly contrary, so are their whole actions, as means, whereby they press to attain to their ends. A good King, thinking his highest honor to consist in the due discharge of his calling, employeth all his study and pains, to procure and maintain, by the making and execution of good Laws, the welfare and peace of his people; and as their natural father and kindly Master, thinketh his greatest contentment standeth in their prosperity, and his greatest surety in having their hearts, subjecting his own private affections and appetites to the weale and standing of his Subjects, ever thinking the common interest his chiefest particular: where by the contrary, an usurping Tyrant, thinking his greatest honor and felicity to consist in attaining per fas, vel nefas to his ambitious pretenses, thinketh never himself sure, but by the dissension and factions among his people, and counterfeiting the Saint while he once creep in credit, will then (by inverting all good Laws to serve only for his unruly private affections) frame the common-weale ever to advance his particular: building his surety upon his peoples misery: and in the end (as a step-father and an uncouth hireling) make up his own hand upon the ruins of the Republic. And according to their actions, so receive they their reward: For a good King (after a happy and famous reign) dieth in peace, lamented by his subjects, and admired by his neighbors; and leaving a reverent renown behind him in earth, obtaineth the Crown of eternal felicity in heaven. And although some of them (which falleth out very rarely) may be cut off by the treason of some unnatural subjects, yet liveth their fame after them, and some notable plague faileth never to overtake the committers in this life, besides their infamy to all posterity hereafter: Where by the contrary, a Tyrant’s miserable and infamous life, armeth in end his own Subjects to become his burreaux: and although that rebellion be ever unlawful on their part, yet is the world so wearied of him, that his fall is little lamented by the rest of his Subjects, and but smiled at by his neighbors. And besides the infamous memory he leaveth behind him here, and the endless pain he sustaineth hereafter, it oft falleth out, that the committers not only escape unpunished, but farther, the fact will remain as allowed by the Law in divers ages thereafter. It is easy then for you (my Son) to make a choice of one of these two sorts of rulers, by following the way of virtue to establish your standing; yea, in case ye fell in the high way, yet should it be with the honorable report, and just regret of all honest men.

And therefore to return to my purpose regarding the government of your Subjects, by making and putting good Laws to execution; I remit the making of them to your own discretion, as ye shall find the necessity of new-rising corruptions to require them: for, ex mais moribus bona leges nata sunt: besides, that in this country, we have already more good Laws than are well executed, and am only to insist in your form of government concerning their execution. Only remember, that as Parliaments have been ordained for making of Laws, so ye abuse not their institution, in holding them for any men’s particulars: For as a Parliament is the most honorable and highest judgement in the land (as being the King’s head Court) if it be well used, which is by making of good Laws in it; so is it the most unjust judgement-seat that may be, being abused to men’s particulars: irrevocable decreits against particular parties, being given therein under color of general Laws, and oft-times the Estates not knowing themselves whom thereby they hurt. And therefore hold no Parliaments, but for necessity of new Laws, which would be but seldom: for few Laws and well put in execution, are best in a well ruled common-weale. As for the matter of forfeitures, which also are done in Parliament, it is not good meddling with these things; but my advice is, ye forfeit none but for such odious crimes as may make them unworthy ever to be restored again: And for smaller offences, ye have other penalties sharp enough to be used against them.

And as for the execution of good Laws, whereat I left, remember that among the differences that I put betwixt the forms of the government of a good King, and an usurping Tyrant; I shew how a Tyrant would enter like a Saint while he found himself fast underfoot, and then would suffer his unruly affections to burst forth. Therefore be ye contrary at your first entry to your Kingdom, to that Quinquennium Neronis, with his tender hearted wish, Vellem nescirem literas, in giving the Law full execution against all breakers thereof but exception. For since ye come not to your reign precario, nor by conquest, but by right and due descent; fear no uproars for doing of justice, since ye may assure your self, the most part of your people will ever naturally favor Justice: providing always, that ye do it only for love to Justice, and not for satisfying any particular passions of yours, under color thereof: otherwise, how justly that ever the offender deserve it, ye are guilty of murder before God: For ye must consider, that God ever looketh to your inward intention in all your actions.

And when ye have by the severity of Justice once settled your countries, and made them know that ye can strike, then may ye thereafter all the days of your life mix Justice with Mercy, punishing or sparing, as ye shall find the crime to have been wilfully or rashly committed, and according to the by-past behavior of the committer. For if otherwise ye declare your clemency at the first, the offences would soon come to such heaps, and the contempt of you grow so great, that when ye would fall to punish, the number of them to be punished, would exceed the innocent; and ye would be troubled to resolve whom-at to begin: and against your nature would be compelled then to wrack many, whom the chastisement of few in the beginning might have preserved. But in this, my over-dear bought experience may serve you for a sufficient lesson: For I confess, where I thought (by being gracious at the beginning) to win all men’s hearts to a loving and willing obedience, I by the contrary found, the disorder of the country, and the loss of my thanks to be all my reward.

But as this severe justice of yours upon all offences would be but for a time, (as I have already said) so is there some horrible crimes that ye are bound in conscience never to forgive: such as Witchcraft, wilful murder, Incest, (especially within the degrees of consanguinity) Sodomy, poisoning, and false coin. As for offences against your own person and authority, since the fault concerneth your self, I remit to your own choice to punish or pardon therein, as your heart serveth you, and according to the circumstances of the turn, and the quality of the committer.

Here would I also add another crime to be unpardonable, if I should not be thought partial: but the fatherly love I bear you, will make me break the bounds of shame in opening it unto you. It is then, the false and irreverent writing or speaking of malicious men against your Parents and Predecessors: ye know the command in God’s law, “Honour your Father and Mother:” and consequently, since ye are the lawful magistrate, suffer not both your Princes and your Parents to be dishonored by any; especially, since the example also toucheth your self, in leaving thereby to your successors, the measure of that which they shall mete out again to you in your like behalf. I grant we have all our faults, which, privately betwixt you and God, should serve you for examples to meditate upon, and mend in your person; but should not be a matter of discourse to others whatsoever. And since ye are come of as honorable Predecessors as any Prince living, repress the insolence of such, as under pretense to tax a vice in the person, seek craftily to stain the race, and to steal the affection of the people from their posterity: For how can they love you, that hated them whom-of ye are come? Wherefore destroy men innocent young sucking Wolves and Foxes, but for the hatred they bear to their race? and why will a colt of a Courser of Naples, give a greater price in a market, than an Ass-colt, but for love of the race? It is therefore a thing monstrous, to see a man love the child, and hate the Parents: as on the other part, the infaming and making odious of the parent, is the readiest way to bring the son in contempt. And for conclusion of this point, I may also allege my own experience: For besides the judgments of God, that with my eyes I have seen fall upon all them that were chief traitors to my parents, I may justly affirm, I never found yet a constant biding by me in all my straits, by any that were of perfect age in my parents days, but only by such as constantly bode by them; I mean specially by them that served the Queen my mother: for so that I discharge my conscience to you, my Son, in revealing to you the truth, I care not, what any traitor or treason-allower think of it.

And although the crime of oppression be not in this rank of unpardonable crimes, yet the over-common use of it in this nation, as if it were a virtue, especially by the greatest rank of subjects in the land, requireth the King to be a sharp censurer thereof. Be diligent therefore to try, and awful to beat down the homes of proud oppressors: embrace the quarrel of the poor and distressed, as your own particular, thinking it your greatest honor to repress the oppressors: care for the pleasure of none, neither spare ye any pains in your own person, to see their wrongs redressed: and remember of the honorable style given to my grand-father of worthy memory, in being called the poor man’s King. And as the most part of a King’s office, standeth in deciding that question of Meum and Tuum, among his subjects; so remember when ye sit in judgement, that the Throne ye sit on is God’s, as Moses saith, and sway neither to the right hand nor to the left; either loving the rich, or pitying the poor. justice should be blind and friendless: it is not there ye should reward your friends, or seek to cross your enemies.

Here now speaking of oppressors and of justice, the purpose leadeth me to speak of Highland and Border oppressions. As for the Highlands, I shortly comprehend them all in two sorts of people: the one, that dwelleth in our main land, that are barbarous for the most part, and yet mixed with some shew of civility: the other, that dwelleth in the isles, and are wholly barbarous, without any sort or shew of civility. For the first sort, put straitly to execution the Laws made already by me against their Over-lords, and the chiefest of their Clans, and it will be no difficulty to subdue them. As for the other sort, follow forth the course that I have intended, in planting Colonies among them of answerable In-lands subjects, that within short time may reform and civilize the best inclined among them; rooting out or transporting the barbarous and stubborn sort, and planting civility in their rooms.

But as for the Borders, because I know, if ye enjoy not this whole Lie, according to God’s right and your lineal descent, ye will never get leave to brook this North and barrenest part thereof; no, not your own head whereon the Crown should stand; I need not in that case trouble you with them: for then they will be the middest of the isle, and so as easily ruled as any part thereof.

And that ye may the readier with wisdom and justice govern your subjects, by knowing what vices they are naturally most inclined to, as a good Physician, who must first know what peccant humours his Patient naturally is most subject unto, before he can begin his cure: I shall therefore shortly note unto you, the principal faults that every rank of the people of this country is most affected unto. And as for England, I will not speak before of them, never having been among them, although I hope in that God, who ever favoureth the right, before I die, to be as well acquainted with their fashions.

As the whole Subjects of our country (by the ancient and fundamental policy of our Kingdom) are divided into three estates, so is every estate hereof generally subject to some special vices; which in a manner by long habitude, are thought rather virtue than vice among them; not that every particular man in any of these ranks of men, is subject unto them, for there is good and evil of all sorts; but that I mean, I have found by experience, these vices to have taken greatest hold with these ranks of men.

And first, that I prejudge not the Church of her ancient privileges, reason would she should have the first place for orders sake, in this catalogue.

The natural sickness that hath ever troubled, and been the decay of all the Churches, since the beginning of the world, changing the candlestick from one to another, as John saith, hath been Pride, Ambition, and Avarice: and now last, these same infirmities wrought the overthrow of the Popish Church, in this country and divers others. But the reformation of Religion in Scotland, being extraordinarily wrought by God, wherein many things were inordinately done by a popular tumult and rebellion, of such as blindly were doing the work of God, but clogged with their own passions and particular respects, as well appeared by the destruction of our themselves and not proceeding from the Princes never as it did in our neighbour country of England, as likewise in Denmark, and sundry parts of Germany; some fiery spirited men in the ministry, got such a guiding of the people at that time of confusion, as finding the gust of government sweet, they began to fantasy to themselves a Democratic form of government: and having (by the iniquity of time) been over well baited upon the wrack, first of my Grandmother, and next of mine own mother, and after usurping the liberty of the time in my long minority, settled themselves so fast upon that imagined as they fed themselves with the hope to become Tribuni plebis: and so in a popular government by leading the people by the nose, to bear the sway of all the rule. And for this cause, there never rose faction in the time of my minority, nor trouble since, but they that were upon that factious part, were ever careful to persuade and allure these unruly spirits among the ministry, to spouse that quarrel as their own: where-through I was ofttimes calumniated in their popular Sermons, not for any evil or vice in me, but because I was a King, which they thought the highest evil. And because they were ashamed to profess this quarrel, they were busy to look narrowly in all my actions; and I warrant you a mote in my eye, yea a false report, was matter enough for them to work upon: and yet for all their cunning, whereby they pretended to distinguish the lawfulness of the office, from the vice of the person, some of them would sometimes snapper out well grossly with the truth of their intentions, informing the people, that all Kings and Princes were naturally enemies to the liberty of the Church, and could never patiently bear the yoke of Christ: with such sound doctrine fed they their flocks. And because the learned, grave, and honest men of the ministry, were ever ashamed and offended with their temerity and presumption, pressing by all good means by their authority and example, to reduce them to a greater moderation; there could be no way found out so meet in their conceit, that were turbulent spirits among them, for maintaining their plots, as parity in the Church: whereby the ignorants were emboldened (as bards) to cry the learned, godly, and modest out of it: parity the mother of confusion, and enemy to Unity, which is the mother of order: For if by the example thereof, once established in the Ecclesiastical government, the Politic and civil estate should be drawn to the like, the great confusion that thereupon would arise may easily be discerned. Take heed therefore (my Son) to such Puritans, very pests in the Church and Common-wealth, whom no deserts can oblige, neither oaths or promises bind, breathing nothing but sedition and calumnies, aspiring without measure, railing without reason, and making their own imaginations (without any warrant of the word) the square of their conscience. I protest before the great God, and since I am here as upon my Testament, it is no place for me to lie in, that ye shall never find with any Highland or Border-thieves greater ingratitude, and more lies and vile perjuries, than with these fanatic spirits: And suffer not the principals of them to brook your land, if ye like to sit at rest; except ye would keep them from trying your patience, as Socrates did an evil wife. And for preservative against their poison, entertain and advance the godly, learned and modest men of the ministry, whom-of (God be praised) there lacketh not a sufficient number: and by their provision to Bishoprics and Benefices (annulling that vile act of Annexation, if ye find it not done to your hand) ye shall not only banish their conceited parity, whereof I have spoken, and their other imaginary grounds; which can neither stand with the order of the Church, nor the peace of a Commonwealth and well ruled Monarchy: but ye shall also re-establish the old institution of three Estates in Parliament, which can no otherwise be done: But in this I hope (if God spare me days) to make you a fair entry, always where I leave, follow ye my steps.

And to end my advice concerning the Church estate, cherish no man more than a good Pastor, hate no man more than a proud Puritan; thinking it one of your fairest styles, to be called a loving nourish-father to the Church, seeing all the Churches within your dominions planted with good Pastors, the Schools (the seminary of the Church) maintained, the doctrine and discipline preserved in purity, according to God’s word, a sufficient provision for their sustentation, a comely order in their policy, pride punished, humility advanced, and they so to reverence their superiors, and their flocks them, as the flourishing of your Church in piety, peace, and learning, may be one of the chief points of your earthly glory, being ever alike ware with both the extremities; as well as ye repress the vain Puritan, so not to suffer proud Papal Bishops: but as some for their qualities will deserve to be preferred before others, so chain them with such bonds as may preserve that estate from creeping to corruption.

The next estate now that by order cometh in purpose, according to their ranks in Parliament, is the Nobility, although second in rank, yet over far first in greatness and power, either to do good or evil, as they are inclined.

The natural sickness that I have perceived this estate subject to in my time, hath been, a feckless arrogant conceit of their greatness and power; drinking in with their very nourish-milk, that their honor stood in committing three points of iniquity: to thrall by oppression, the meaner sort that dwelleth near them, to their service and following, although they hold nothing of them: to maintain their servants and dependents in any wrong, although they be not answerable to the laws (for any body will maintain his man in a right cause) and for any displeasure, that they apprehend to be done unto them by their neighbour, to take up a plain feud against him; and (without respect to God, King, or common-weale) to bang it out bravely, he and all his kin, against him and all his: yea they will think the King farre in their common, in-case they agree to grant an assurance to a short day, for keeping of the peace: where, by their natural duty, they are obliged to obey the law, and keep the peace all the days of their life, upon the peril of their very necks.

For remedy to these evils in their estate, teach your Nobility to keep your laws as precisely as the meanest: fear not their muttering or being discontented, as long as ye rule well; for their pretended reformation of Princes taketh never effect, but where evil government precedeth. Acquaint your self so with all the honest men of your Barons and Gentlemen, and be in your giving access so open and affable to every rank of honest persons, as may make them ready without scarring at you, to make their own suites to you themselves, and not to employ the great Lords their intercessors; for intercession to Saints is Papistry: so shall ye bring to a measure their monstrous backs. And for their barbarous feuds, put the laws to due execution made by me there-anent; beginning ever soonest at him that ye love best, and is most obliged unto you; to make him an example to the rest. For ye shall make all your reformations to begin at your elbow, and so by degrees to flow to the extremities of the land. And rest not, until ye root out these barbarous feuds; that their effects may be as well smothered down, as their barbarous name is unknown to any other nation: For if this Treatise were written either in French or Latin, I could not get them named unto you but by circumlocution. And for your easier abolishing of them, put sharply to execution my laws made against Guns and traitorous Pistolets; thinking in your heart, tearming in your speech, and using by your punishments, all such as wear and use them, as brigands and cut-throats.

On the other part, eschew the other extremity, in lightlying and contemning your Nobility. Remember how that error brake the King my grand-father’s heart. But consider that virtue followeth oftest noble blood: the worthiness of their ancestors craveth a reverent regard to be had unto them: honour them therefore that are obedient to the law among them, as Peers and Fathers of your land: the more frequently that your Court can be garnished with them, think it the more your honour; acquainting and employing them in all your greatest affaires; sen it is, they must be your arms and executers of your laws: and so use your self lovingly to the obedient, and rigorously to the stubborn, as may make the greatest of them to think, that the chiefest point of their honour, standeth in striving with the meanest of the land in humility towards you, and obedience to your Laws: beating ever in their ears, that one of the principal points of service that ye crave of them, is, in their persons to practice, and by their power to procure due obedience to the Law, without the which, no service they can make, can be agreeable unto you.

But the greatest hindrance to the execution of our Laws in this country, are these heritable Sheriffdoms and Regalities, which being in the hands of the great men, do wrack the whole country:

For which I know no present remedy, but by taking the sharper account of them in their Offices; using all punishment against the slothful, that the Law will permit: and ever as they vaike, for any offences committed by them, dispose them never heritably again: pressing, with time, to draw it to the laudable custom of England: which ye may the easier do, being King of both, as I hope in God ye shall.

And as to the third and last estate, which is our Burghers (for the small Barons are but an inferior part of the Nobility and of their estate) they are composed of two sorts of men; Merchants and Crafts-men: either of these sorts being subject to their own infirmities.

The Merchants think the whole common-wealth ordained for making them up; and accounting it their lawful game and trade, to enrich themselves upon the loss of all the rest of the people, they transport from us things necessary; bringing back sometimes unnecessary things, and at other times nothing at all. They buy for us the worst wares, and sell them at the dearest prices: and albeit the victuals fall or rise of their prices, according to the abundance or scantness thereof; yet the prices of their wares ever rise, but never fall: being as constant in that their evil custom, as if it were a settled Law for them. They are also the special cause of the corruption of the coin, transporting all our own, and bringing in foreign, upon what price they please to set on it: For order putting to them, put the good Laws in execution that are already made concerning these abuses; but especially do three things: Establish honest, diligent, but few Searchers, for many hands make slight work; and have an honest and diligent Treasurer to take count of them: Permit and allure foreign Merchants to trade here: so shall ye have best and best cheap wares, not buying them at the third hand: And set every year down a certain price of all things; considering first, how it is in other countries: and the price being set reasonably down, if the Merchants will not bring them home on the price, cry foreigners free to bring them.

And because I have made mention here of the coin, make your money of fine Gold and Silver; causing the people be payed with substance, and not abused with number: so shall ye enrich the common-wealth, and have a great treasure laid up in store, if ye fall in wars or in any straits: For the making it baser, will breed your commodity; but it is not to be used, but at a great necessity.

And the Craftsmen think, we should be content with their work, how bad and dear soever it be: and if they in any thing be controlled, up goeth the blew-blanket (it is perceived as an attack upon their privileges; Ed. note): But for their part, take example by ENGLAND, how it hath flourished both in wealth and policy, since the strangers Crafts-men came in among them: Therefore not only permit, but allure strangers to come near also; taking as strait order for repressing the mutinying of ours at them, as was done in ENGLAND, at their first in-bringing there.

But unto one fault is all the common people of this Kingdom subject, as well burgh as land; which is, to judge and speak rashly of their Prince, setting the Common-wealth upon four props, as we call it; ever wearying of the present estate, and desirous of novelties. For remedy whereof (besides the execution of Laws that are to be used against irreverent speakers) I know no better mean, than so to rule, as may justly stop their mouths from all such idle and irreverent speeches; and so to prop the weale of your people, with provident care for their good government, that justly, Momus himself may have no ground to grudge at: and yet so to temper and mix your severity with mildness, that as the unjust railers may be restrained with a reverent awe; so the good and loving Subjects, may not only hue in surety and wealth, but be stirred up and invited by your benign courtesies, to open their mouths in the just praise of your so well moderated regiment. In respect whereof, and therewith also the more to allure them to a common amity among themselves, certain days in the year would be appointed, for delighting the people with public spectacles of all honest games, and exercise of arms: as also for convening of neighbours, for entertaining friendship and hearthiness, by honest feasting and merriness: For I cannot see what greater superstition can be in making plays and lawful games in May, and good cheer at Christmas, than in eating fish in Lent, and upon Fridays, the Papists as well using the one as the other: so that always the Sabbaths be kept holy, and no unlawful pastime be used: And as this form of contenting the peoples minds, hath been used in all well governed Republics: so will it make you to perform in your government that old good sentence,

Omne tulit punctum, qui miscuit vtile dulci.

Ye see now (my Son) how for the zeal I bear to acquaint you with the plain and single verity of all things, I have not spared to be something Satyric, in touching well quickly the faults in all the estates of my kingdom: But I protest before God, I do it with the fatherly love that I owe to them all; only hating their vices, whereof there is a good number of honest men free in every estate.

And because, for the better reformation of all these abuses among your estates, it will be a great help unto you, to be well acquainted with the nature and humours of all your Subjects, and to know particularly the estate of every part of your dominions; would therefore counsel you, once in the year to visit the principal parts of the country, ye shall be in for the time: and because I hope ye shall be King of more countries than this; once in the three years to visit all your Kingdoms; not trusting to Viceroys, but hearing your self their complaints; and having ordinary Counsels and justice-seats in every Kingdom, of their own countrymen: and the principal matters ever to be decided by your self when ye come in those parts.

Ye have also to consider, that ye must not only be careful to keep your subjects, from receiving any wrong of others within; but also ye must be careful to keep them from the wrong of any foreign Prince without: since the sword is given you by God not only to revenge upon your own subjects, the wrongs committed amongst themselves; but further, to revenge and free them of foreign injures done unto them: And therefore wars upon just quarrels are lawful: but above all, let not the wrong cause be on your side.

Use all other Princes, as your brethren, honestly and kindly: Keep precisely your promise unto them, although to your hurt: Strive with every one of them in courtesy and thankfulness: and as with all men, so especially with them, be plain and truthful; keeping ever that Christian rule, to do as ye would be done to: especially in counting rebellion against any other Prince, a crime against your own self, because of the preparative. Supply not therefore, nor trust not other Princes rebels; but pity and succor all lawful Princes in their troubles. But if any of them will not notwithstanding whatsoever your good deserts, to wrong you or your subjects, crave redress at leisure; hear and do all reason: and if no offer that is lawful or honourable, can make him to abstain, nor repair his wrong doing; then for last refuge, commit the justness of your cause to God, giving first honestly up with him, and in a public and honourable form.

But omitting now to teach you the form of making wars, because that art is largely treated of by many, and is better learned by practice than speculation; I will only set down to you near a few precepts therein. Let first the justness of your cause be your greatest strength; and then omit not to use all lawful means for backing of the same. Consult therefore with no Necromancer nor false Prophet, upon the success of your wars, remembering on king Saul’s miserable end: but keep your land clean of all South-sayers, according to the command in the Law of God, dictated by Jeremiah. Neither commit your quarrel to be tried by a Duel: for beside that generally all Duel appeareth to be unlawful, committing the quarrel, as it were, to a lot; whereof there is no warrant in the Scripture, since the abrogating of the old Law: it is specially most unlawful in the person of a King; who being a public person hath no power therefore to dispose of himself, in respect, that to his preservation or fall, the safety or wrack of the whole commonweal is necessarily coupled, as the body is to the head.

Before ye take on war, play the wise Kings part described by Christ; fore-seeing how ye may bear it out with all necessary provision especially remember, that money is Neruus belli. Choose old experimented Captains, and young able soldiers. Be extremely strait and severe in martial Discipline, as well for keeping of order, which is as requisite as hardiness in the wars, and punishing of sloth, which at a time may put the whole army in hazard; as likewise for repressing of mutinies, which in wars are wonderful dangerous. And look to the Spaniard, whose great success in all his wars, hath only come through straitness of Discipline and order: for such errors may be committed in the wars, as cannot be gotten mended again.

Be in your own person wakeful, diligent, and painful; using the advice of such as are skilfulness in the craft, as ye must also do in all other. Be homely with your soldiers as your companions, for winning their hearts; and extremely liberal, for then is no time of sparing. Be cold and foreseeing in devising, constant in your resolutions, and forward and quick in your executions. Fortify well your Camp, and assail not rashly without an advantage: neither fear not lightly your enemy. Be curious in devising stratagems, but always honestly: for of any thing they work greatest effects in the wars, if secrecy be joined to invention. And once or twice in your own person hazard your self fairly; but, having acquired so the fame of courage and magnanimity, make not a daily soldier of your self, exposing rashly your person to every peril: but conserve your self thereafter for the weale of your people, for whose sake ye must more care for your self, than for your own.

And as I have counseled you to be slow in taking on a war, so advise I you to be slow in peace-making. Before ye agree, look that the ground of your wars be satisfied in your peace; and that ye see a good surety for you and your people: otherwise a honourable and just war is more tolerable, than a dishonorable and dis-advantageous peace.

But it is not enough to a good King, by the scepter of good Laws well execute to govern, and by force of arms to protect his people; if he join not therewith his virtuous life in his own person, and in the person of his Court and company; by good example alluring his Subjects to the love of virtue, and hatred of vice. And therefore (my Son) since all people are naturally inclined to follow their Princes example (as I shewed you before) let it not be said, that ye command others to keep the contrary course to that, which in your own person ye practice, making so your words and deeds to fight together: but by the contrary, let your own life be a law-book and a mirror to your people; that therein they may read the practice of their own Laws; and therein they may see, by your image, what life they should lead.

And this example in your own life and person, I likewise divide in two parts: The first, in the government of your Court and followers, in all godliness and virtue: the next, in having your own mind decked and enriched so with all virtuous qualifies, that therewith ye may worthily rule your people: For it is not enough that ye have and retain (as prisoners) within your self never so many good qualities and virtues, except ye employ them, and set them on work, for the weale of them that are committed to your charge:

Virtutis enim laus omnis in actione consistit.

First then, as to the government of your Court and followers, King David sets down the best precepts, that any wise and Christian King can practice in that point: For as ye ought to have a great care for the ruling well of all your Subjects, so ought ye to have a double care for the ruling well of your own servants; since unto them ye are both a Politic and Economic governor. And as every one of the people will delight to follow the example of any of the Courtiers, as well in evil as in good; so what crime so horrible can there be committed and over-seen in a Courtier, that will not be an exemplary excuse for any other boldly to commit the like? And therefore in two points have ye to take good heed concerning your Court and household: first, in choosing them wisely; next, in carefully ruling them whom ye have chosen.

It is an old and true saying, That a kindly cart-horse will never become a good horse: for albeit good education and company be great helps to Nature, and education be therefore most justly called altera natura, yet is it evil to get out of the flesh, that is bred in the bone, as the old proverb saith. Be very ware then in making choice of your servants and company; Nam Turpius eiicitur quam non admittitur hospes: and many respects may lawfully let an admission, that will not be sufficient causes of deprivation.

All your servants and Court must be composed partly of minors, such as young Lords, to be brought up in your company, or Pages and such like; and partly of men of perfect age, for serving you in such rooms, as ought to be filled with men of wisdom and discretion. For the first sort, ye can do no more, but choose them within age, that are come of a good and virtuous kind, In fide parentum, as Baptism is used: For though anima non venit ex traduce, but is immediately created by God, and infused from above; yet it is most certain, that virtue or vice will oftentimes, with the heritage, be transferred from the parents to the posterity, and run on a blood (as the Proverb is) the sickness of the mind becoming as kindly to some races, as these sicknesses of the body, that infect in the seed: Especially choose such minors as are come of a true and honest race, and have not had the house whereof they are descended, infected with falsehood.

And as for the other sort of your company and servants, that ought to be of perfect age; first see that they be of a good fame and without blemish; otherwise, what can the people think, but that ye have chosen a company unto you, according to your own humour, and so have preferred these men, for the love of their vices and crimes, that ye knew them to be guilty of? For the people that see you not within, cannot judge of you, but according to the outward appearance of your actions and company, which only is subject to their sight: And next, see that they be indued with such honest qualities, as are meet for such offices, as ye ordain them to serve in; that your judgement may be known in employing every man according to his gifts: And shortly, follow good king David’s counsel in the choice of your servants, by setting your eyes upon the faithful and upright of the land to dwell with you.

But here I must not forget to remember, and according to my fatherly authority, to charge you to prefer specially to your service, so many as have truly served me, and are able for it: the rest, honourably to reward them, preferring their posterity before others, as kindliest: so shall ye not only be best served, (for if the haters of your parents cannot love you, as I shewed before, it followeth of necessity their lovers must love you) but further, ye shall make known your thankful memory of your father, and procure the blessing of these old servants, in not missing their old master in you; which otherwise would be turned in a prayer for me, and a curse for you. Use them therefore when God shall call me, as the testimonies of your affection towards me; trusting and advancing those farthest, whom I found most faithful: which ye must not discern by their rewards at my hand (for rewards, as they are called Bona fortunce, so are they subject unto fortune) but according to the trust I gave them; having oft-times had better heart than hap to the rewarding of sundry; And on the other part, as I wish you to declare your constant love towards them that I loved, so desire I you to make known in the same measure, your constant hatred to them that I hated: I mean, bring not home, nor restore not such, as ye find standing banished or fore-faulted by me. The contrary would indicate in you over great a contempt of me, and lightness in your own nature: for how can they be true to the Son, that were false to the Father?

But to return to the purpose concerning the choice of your servants, ye shall by this wise form of doing, eschew the inconvenients, that in my minority I fell in, concerning the choice of my servants: For by them that had the command where I was brought up, were my servants put unto me; not choosing them that were most meet to serve me, but whom they thought most meet to serve their turn about me, as declared well in many of them at the first rebellion raised against me, which compelled me to make a great alteration among my servants. And yet the example of that corruption made me to be long troubled there-after with solicitors, recommending servants unto me, more for serving in effect, their friends that put them in, than their master that admitted them. Let my example then teach you to follow the rules here set down, choosing your servants for your own use, and not for the use of others; And since ye must be communis parens to all your people, so choose your servants indifferently out of all quarters; not respecting other mens appetites, but their own qualities: For as ye must command all, so reason would, ye should be served out of all, as ye please to make choice.

But specially take good heed to the choice of your servants, that ye prefer to the offices of the Crown and estate: for in other offices ye have only to take heed to your own weale; but these concern likewise the weale of your people, for the which ye must be answerable to God. Choose then for all these Offices, men of known wisdom, honesty, and good conscience; well practiced in the points of the craft, that ye ordain them for, and free of all factions and partialities; but specially free of that filthy vice of Flattery, the pest of all Princes, and wrack of Republics: For since in the first part of this Treatise, I fore-warned you to be at war with your own inward flatterer filautiva, how much more should ye be at war with outward flatterers, who are nothing so sib to you, as your self is; by the selling of such counterfeit wares, only pressing to ground their greatness upon your ruins? And therefore be careful to prefer none, as ye will be answerable to God but only for their worthiness: But specially choose honest, diligent, mean, but responsible men, to be your receivers in money matters: mean I say, that ye may when ye please, take a sharp account of their intromission, without peril of their breeding any trouble to your estate: for this oversight hath been the greatest cause of my misthriving in money matters. Especially, put never a foreigner, in any principal office of estate: for that will never fail to stir up sedition and envy in the country-men’s hearts, both against you and him: But (as I said before) if God provide you with more countries than this; choose the born-men of every country, to be your chief counselors therein.

And for conclusion of my advice addressing the choice of your servants, delight to be served with men of the noblest blood that may be had: for besides that their service shall breed you great good-will and least envy, contrary to that of start-ups; ye shall oft find virtue follow noble races, as I have said before speaking of the Nobility.

Now, as to the other point, concerning your governing of your servants when ye have chosen them; make your Court and company to be a pattern of godliness and all honest virtues, to all the rest of the people. Be a daily watch-man over your servants, that they obey your laws precisely: For how can your laws be kept in the country, if they be broken at your ear? Punishing the breach thereof in a Courtier, more severely, than in the person of any other of your subjects: and above all, suffer none of them (by abusing their credit with you) to oppress or wrong any of your subjects. Be homely or strange with them, as ye think their behavior deserveth, and their nature may bear with. Think a quarrellous man a pest in your company. Be careful ever to prefer the gentlest natured and trustiest, to the most close Offices about you, especially in your chamber. Suffer none about you to meddle in any men’s particulars, but like the Turks Janissaries, let them know no father but you, nor particular but yours. And if any will meddle in their kin or friends quarrels, give them their leave: for since ye must be of no surname nor kin, but equal to all honest men; it becometh you not to be followed with partial or factious servants. Teach obedience to your servants, and not to think themselves over-wise: and, as when any of them deserveth it, ye must not spare to put them away, so, without a seen cause, change none of them. Pay them, as all others your subjects, with præmium or poena as they deserve, which is the very ground-stone of good government. Employ every man as ye think him qualified, but use not one in all things, lest he wax proud, and be envied of his fellows. Love them best, that are plainest with you, and disguise not the truth for all their kin: suffer none to be evil tongued, nor backbiters of them they hate: command a heartily and brotherly love among all them that serve you. And shortly, maintain peace in your Court, banish envy, cherish modesty, banish debased insolence, foster humility, and repress pride: setting down such a comely and honourable order in all the points of your service; that when strangers shall visit your Court, they may with the Queen of Sheba, admire your wisdom in the glory of your house; and comely order among your servants.

But the principal blessing that ye can get of good company, will stand in your marrying of a godly and virtuous wife: for she must be nearer unto you, than any other company, being Flesh of your flesh, and bone of your bone, as Adam said of Eve. And because I know not but God may call me, before ye be ready for Marriage; I will shortly set down to you here my advice therein.

First of all consider, that Marriage is the greatest earthly felicity or misery, that can come to a man, according as it pleaseth God to bless or curse the same. Since then without the blessing of GOD, ye cannot look for a happy success in Marriage, ye must be careful both in your preparation for it, and in the choice and usage of your wife, to procure the same. By your preparation, I mean, that ye must keep your body clean and unpolluted, till ye give it to your wife, whom-to only it belongeth. For how can ye justly crave to be joined with a pure virgin, if your body be polluted? why should the one half be clean, and the other defiled? And although I know, fornication is thought but a light and venial sin, by the most part of the world, yet remember well what I said to you in my first Book concerning conscience; and count every sin and breach of God’s law, not according as the vain world esteemeth of it, but as God the judge and maker of the law accounteth of the same. Hear God commanding by the mouth of Paul, to abstain from fornication, declaring that the fornicator shall not inherit the Kingdom of heaven: and by the mouth of John, reckoning out fornication amongst other grievous sins, that debarre the committers amongst dogs and swine, from entry in that spiritual and heavenly Jerusalem. And consider, if a man shall once take upon him, to count that light, which God calleth heavy; and venial that, which God calleth grievous; beginning first to measure any one sin by the rule of his lust and appetites, and not of his conscience; what shall let him to do so with the next, that his affections shall stir him to, the like reason serving for all: and so to go forward till he place his whole corrupted affections in God’s room? And then what shall come of him; but, as a man given over to his own filthy affections, shall perish into them? And because we are all of that nature, that closely related examples touch us nearest, consider the difference of success that God granted in the Marriages of the King my grand-father, and me your own father: the reward of his incontinence, (proceeding from his evil education) being the sudden death at one time of two pleasant yong Princes; and a daughter only born to succeed to him, whom he had never the chance, so much as once to see or bless before his death: leaving a double curse behind him to the land, both a Woman of sex, and a newborn babe of age to reign over them. And as for the blessing God hath bestowed on me, in granting me both a greater continence, and the fruits following there-upon, your self, and kin folks to you, are (praise be to God) sufficient witnesses: which, I hope the same God of his infinite mercy, shall continue and increase, without repentance to me and my posterity. Be not ashamed then, to keep clean your body, which is the Temple of the holy Spirit, notwithstanding all vain allurements to the contrary, discerning truly and wisely of every virtue and vice, according to the true qualities thereof, and not according to the vain conceits of men.

As for your choice in Marriage, respect chiefly the three causes, wherefore Marriage was first ordained by God; and then join three accessories, so far as they may be obtained, not derogating to the principles.

The three causes it was ordained for, are, for staying of lust, for procreation of children, and that man should by his Wife, get a helper like himself. Defer not then to Marry till your age: for it is ordained for quenching the lust of your youth: Especially a King must in good time Marry for the weale of his people. Neither Marry ye, for any accessory cause or worldly respects, a woman unable, either through age, nature, or accident, for procreation of children: for in a King that were a double fault, as well against his own weale, as against the weale of his people. Neither also Marry one of known evil conditions, or vicious education: for the woman is ordained to be a helper, and not a hinderer to man.

The three accessories, which as I have said, ought also to be respected, without derogating to the principal causes, are beauty, riches, and friendship by alliance, which are all blessings of God. For beauty increaseth your love to your Wife, contenting you the better with her, without caring for others: and riches and great alliance, do both make her the abler to be a helper unto you. But if over great respect being had to these accessories, the principal causes be over-seen (which is over oft practiced in the world) as of themselves they are a blessing being well used; so the abuse of them will turn them in a curse. For what can all these worldly respects avail, when a man shall find himself coupled with a devil, to be one flesh with him, and the half marrow in his bed? Then (though too late) shall he find that beauty without bounty, wealth without wisdom, and great friendship without grace and honesty; are but fair shows, and the deceitful masques of infinite miseries.

But have ye respect, my Son, to these three special causes in your Marriage, which flow from the first institution thereof, & cætera omnia adijcientur vobis. And therefore I would soonest have you to Marry one that were fully of your own Religion; her rank and other qualities being agreeable to your estate. For although that to my great regret, the number of any Princes of power and account, professing our Religion, be but very small; and that therefore this advice seems to be the more strait and difficult: yet ye have deeply to weigh, and consider upon these doubts, how ye and your wife can be of one flesh, and keep unity betwixt you, being members of two opposite Churches: disagreement in Religion bringeth ever with it, disagreement in manners; and the dissension betwixt your Preachers and her’s, will breed and foster a dissension among your subjects, taking their example from your family; besides the peril of the evil education of your children. Neither pride you that ye will be able to frame and make her as ye please: that deceived Solomon the wisest King that ever was; the grace of Perseverance, not being a flower that groweth in our garden.

Remember also that Marriage is one of the greatest actions that a man doeth in all his time, especially in taking of his first Wife: and if he Marry first basely beneath his rank, he will ever be the less accounted of thereafter. And lastly, remember to choose your Wife as I advised you to choose your servants: that she be of a whole and clean race, not subject to the hereditary sicknesses, either of the soul or the body: For if a man will be careful to breed horses and dogs of good kinds, how much more careful should he be, for the breed of his own loins? So shall ye in your Marriage have respect to your conscience, honour, and natural weale in your successors.

When ye are Married, keep inviolably your promise made to God in your Manage; which standeth all in doing of one thing, and abstaining from another: to treat her in all things as your wife, and the half of your self; and to make your body (which then is no more yours, but properly hers) common with none other. I trust I need not to insist here to dissuade you from the filthy vice of adultery: remember only what solemn promise ye make to God at your Marriage: and since it is only by the force of that promise that your children succeed to you, which otherwise they could not do; equity and reason would, ye should keep your part thereof. God is ever a severe avenger of all perjuries; and it is no oath made in jest, that giveth power to children to succeed to great kingdoms.

Have the King my grand-father’s example before your eyes, who by his adultery, bred the wrack of his lawful daughter and heir; in begetting that bastard, who unnaturally rebelled, and procured the ruin of his own Sovereign and sister. And what good her posterity hath gotten since, of some of that unlawful generation, Bothuell his treacherous attempts can bear witness. Keep precisely then your promise made at Marriage, as ye would wish to be partaker of the blessing therein.

And for your behavior to your Wife, the Scripture can best give you counsel therein: Treat her as your own flesh, command her as her Lord, cherish her as your helper, rule her as your pupil, and please her in all things reasonable; but teach her not to be curious in things that belong her not: Ye are the head, she is your body; It is your office to command, and hers to obey; but yet with such a sweet harmony, as she should be as ready to obey, as ye to command; as willing to follow, as ye to go before; your love being wholly knit unto her, and all her affections lovingly bent to follow your will.

And to conclude, keep specially three rules with your Wife: first, suffer her never to meddle with the Political government of the Commonweal, but hold her at the Economic rule of the house: and yet all to be subject to your direction: keep carefully good and chaste company about her, for women are the frailest sex; and be never both angry at once, but when ye see her in passion, ye should with reason subdue yours: for both when ye are settled, ye are meetest to judge of her errors; and when she is come to her self, she may be best made to apprehend her offence, and reverence your rebuke.